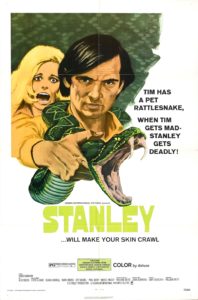

Obiwanishinaabe’s Spoiler-Filled Review of William Grefe’s “Stanley” (1972)

There are two places in the US that draw people wanting to see bizarre theme parks, experience outrageous night life, enjoy salt water beaches, and perhaps build a new life of luxury. One is California, which draws people who think that they have enough talent, innovation, beauty, or creativity to become famous. The other is Florida, which draws people who lack precisely those things. Florida, to me anyways, is for dreamers who lack imagination. So it is no wonder that “Stanley” is not a Hollywood picture; it was made in the Everglades. I only watched it once, please note, and I won’t take the time to get exact quotes for this review.

“Stanley” is the story of a mixed-blood Seminole named Tim Ochopee (Chris Robinson, a nonnative unrelated to the Black Crowes singer). It is now six months after his return from Vietnam, where he grew weary of “The white man telling the Red man to kill the Yellow man.” Unable to readjust to civilian or Seminole life, he has shacked himself up deep in the swamp where he makes money selling snake venom to an antidote clinic. A feature that went unnoticed elsewhere, Tim’s affinity with snakes must be attributable to his being Seminole (the “Indians are so in touch with nature” stereotype). It also seems that he drinks snake venom from a large kettle in his kitchen; he drinks it after being bitten outside, and I think that a scene in which the girl is holding the ladle and only brings it to her mouth without drinking was supposed to provide some tension. The film never says what’s in the pot.

Tim does collect and keeps plenty of snakes, including the title character Stanley, and Stanley’s “wife” Hazel, who are both rattlers. At one point, the trio share a thanksgiving meal in honor of three baby snakes born to the happy couple. The table talk turns to Tim wishing the snakes could be vegetarians, because as animals, they should understand that eating animals is wrong. As we see Stanley swallowing a live mouse, Stanley telepathically (?) reminds Tim that humans are also animals, and humans certainly don’t know any better.

Because he has largely rejected humanity, Tim spends most of his words on snakes. Two Seminole relatives visit him in the first sequence, inviting him to move back to the village, or at least attend the Green Corn Dance. They ask him to come home so he can find a wife and have some kids, so that the tribe can “carry on for a few more decades.” Yes, once again we are treated to the Vanishing Race stereotype, but in this case the tragedy extends beyond the Seminole and to include Americans as a “race.”

Or at least Floridians.

Everyone else in the film has a terrible life, except maybe the doctor at the snake venom clinic (Gary Crucher, who also wrote the screenplay, which may explain it). A local crime boss (Alex Rocco) who seems to have attained that status through animal poaching) wants to enlist Tim in the snakeskin trade. When Tim refuses, that sets the henchmen against him, just like they were against Tim’s father. One of the henchmen is also sexing up the crime boss’s daughter (Susan Carroll), who is too flat of a character to read as having any agency, and so can only be taken to be slutty. Her own father is ambivalent about her sexual transgressions; at one point he is threatening the henchman to stay away from her, while at another he is floating in his backyard pool, stroking her bare leg, and commenting on how attractive she is getting to be. She is 17 years old, and her mother ran off with come other man, leaving the crime boss bereft. He overcompensates by tightening his tenuous hold on his criminal animal pelt and clothing emprire through strong-arm violence, smoking cigars, and doing arm curls with 2 pound dumbbells while posing in front of a mirror by his pool. Well past his prime, and deteriorating in seemingly every way, he is just as lost and pathetic as Tim.

There is a rather bizarre subplot involving an aged burlesque dancer (Marcie Knight). She is married to the club owner, and her act is not bringing in customers like it used to. The club owner (Rey Baumel) berates her for being “over the hill,” and he, like the crime boss, is shown posing and preening, telling himself that he’s still in good shape as he has convinced his drunken wife to spend the night with him at the club.

The dancer uses snakes that Tim has caught, dancing erotically with them on stage. Tim asks her to be gentle with them, and she has been, knowing that Tim comes by the club to check out his snakes during her act. The club owner, however, has made no such promise, and instead hatches a plan to bring in customers by having his wife finish her dance by biting the head off the snake. His plan is a success, and soon she is “Packing ’em in, just like she used to.”

Oh, and at some point some mod/hippie character–who wears John Lennon shades, striped pants, and is whacked out of his mind on some sort of drug(s)–shows up to kill Hazel and her three kids.

With all these tensions developing, with every character either set against Tim directly or set up to betray him by disrespecting the snakes, we are then shown how Tim punishes each trespass by taking his snakes to kill the transgressors.

Up until this point, the film can be said to be an allegory for the failure of the American dream. The Vietnam war, economic downturns, and the erosion of tribal unity all combine into comment on America itself being well past its prime.

Or at least Florida.

But it doesn’t end with Tim finally able to restore justice through the killing of the animal-poaching, clothing-designer mastermind. Tim is not Billy Jack, that other mixed-blood character who delivered vigilante justice by mixing primitivist violence with Noble Savage philosophy. Primitivism is the use of “Natural Reason” or pastoral simplicity to comment on how Civilization has somehow made authentic, unifying human interactions difficult or impossible. Tim is not The Savage as cultural critic of the Civlized. Instead, Tim succumbs to domineering excesses and self-absorption. After his snakes kill the crime boss, Tim knocks the daughter unconscious and takes her back to his “Garden of Eden.” After being carried off, she isn’t shown struggling or trying to escape. In fact, we are told that during their hours-long trip to his shack, he tells her about his Vietnam experience, the death of his father, and probably everything else that is wrong with his life, and that seems to have been enough to convice her that Tim is an OK guy to be around.

Even after being kidnapped, she is still open to having sex with him so long as he doesn’t just say that he likes her. She wants him to tell her that he loves her. Clearly, she has some intimacy issues.

He says that “like will have to be good enough,” and apparently that worked for her. But upon waking, she wants to leave, and Tim won’t allow that. Tim makes it clear that he wants to keep her, procreate, and raise the kids to hate humans. Tim starts breaking down, his identity issues coming to the fore, as he says that he doesn’t “feel like an Indian, doesn’t feel like a White man, and doesn’t even feel human at all.” Chaos ensues. He confesses that he dreams of being a snake, tries to sic his snakes on her, and instead they bite him because they know better. A fire breaks out, and after she escapes he stumbles out, badly burned, blackened and shedding his skin. He crawls through the mud, his dream finally almost fulfilled, and says “Maybe in Hell I’ll finally find out what I am” before dying.

Unlike many grindhouse films, “Stanley” was almost devoid of humor. I was left feeling mostly sad and a little bit disgusted. Here, it was a reaction to the pathetic lives of the characters and, mostly, disappointment at the very real violence against not just the mice but the snakes. We see the baby snakes crushed with the butt of a rifle, we see a snake shot, and we see Tim swinging snakes around in a tantrum, smashing their bodies against the cabinets and floor in his kitchen, as well as onto the bodies of snakes moving around him on the floor. There is a higher snake body count than human.

The DVD extras include a great “making of” documentary where we learn how the script writer was chosen because he was a known pill-head and would stay up for 72 hours straight to meet the shooting deadline. I guess he deserves some credit for knowing a tribal name and accurate location, as well as being able to reference the Green Corn Dance, but it’s depressing that we’re not used to even this low level of accuracy when it comes to Indigenous representation.